SAFETY

ADVICE

Situational Awareness (S/A)

By practicing situational awareness every day, contractors can keep themselves and others safe while on the job.

If I could only train the building trades one safety subject, it would be Situational Awareness (S/A). I have implemented many situational awareness techniques throughout my own life. As a teenage worker commuting after second shift from South Boston out to the suburbs, I trained two days a week (pre-Krav Maga) in S/A and self-defense techniques. This new skill set enabled me to escape several high-risk situations relatively unscathed in order to “reach home safely” (objective). And shouldn’t that be our primary objective on the job?

As a professional, cross-country flatbed driver, hauling hazardous and oversized loads, I was trained by my partner/mentor to remain mentally active and continuously observant of environmental conditions and difficult traffic situations as they evolved and devolved every 60 seconds. His observation mantra was: Windshield, right mirror, windshield, gauges, windshield, left mirror, windshield (repeat). Even with over 5 million miles of experience, he said every day driving was still an awareness training day.

I have incorporated many of the S/A techniques I’ve learned in the past within my own safety training classes, particularly in high-risk activities such as entering confined spaces, working with hazardous materials and performing tasks at extreme height. Multi-employer construction job sites can also present particularly well disguised, high-risk environments in which to work. If workers are not particularly aware of observable details, acts and conditions on their specific worksite, they are unprepared to react using pre-determined responses adapted to the situation and tools-at-hand. Without a plan to act, the consequences will be startingly uncontrolled and potentially dangerous. The threat may not come from a midnight gang of urban muggers experienced in blitzkrieg ambush, but rather, commonplace and accumulating construction hazards that were either taken for granted and/or totally ignored.

I find many parallels between the unaware pedestrian wandering deep into a strange neighborhood and a construction or demolition worker who has failed to exercise even minimum situational awareness. The adversarial mechanism at work in both examples is similar in set-up, deployment, reaction and outcome. It all originates from personal neglect and results in violent consequences.

Like a gang of muggers, the accelerating speed of the assault compounded by the degree of resulting violence can overwhelm the victim’s mind, dulling the senses and canceling critical reaction time, especially if you’re not prepared with a plan and well-practiced in its deployment. For instance, roofers who choose not to design and implement a site-specific Fall Protection Plan will seldom evaluate their risks of falling off of a steep-pitched roof, or what must be done in preparation for just such a likely event. Without any forethought, most are inexperienced in the violence and chaos ensuing after a fall of one or more roofers, including the post-fall rescue problems that inevitably occur without pre-planned solutions. Statistics prove that more persons are injured and killed while attempting a rescue operation without adequate training and preparation, than the original victims.

There are many occupations that regularly and deliberately prepare their workforce in specific risk prevention and mitigation tactics, which initially train S/A as a prerequisite foundation. These include the five branches of the military, fire service, police, EMTs, search and rescue, divers, NASA, commercial drivers, and commercial pilots, to name just a few. There are a great number of basic S/A training models in professional use today that describe the actions (offense) and reactions (defense) required for survival of either an individual, team or system.

Richar D.

ALANIZ

Chip

Macdonald

Photo credit: South_agency/E+ via Getty Images

SCROLL

DOWN

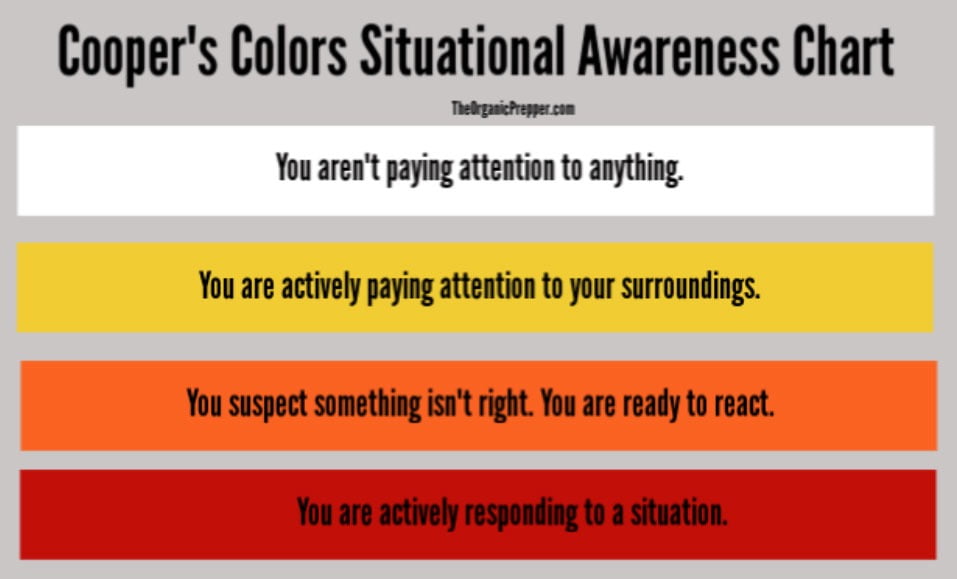

Cooper’s Four-Level S/A System

John Dean “Jeff” Cooper (1920–2006) was a decorated U.S. Marine Sharpshooter, founder of the Gunsite Academy and creator of the modern technique of handgun shooting. He also is credited with developed the “Four Alert Levels of Situational Awareness.”

WHITE: Unaware Level

Person is unaware of any threat that may target them

Person is unprepared/unready for any appropriate decisive action

Lowest level of awareness on physical/psychological level

Heart Beat: 60-80 BPM

Example: Walking and texting simultaneously

YELLOW: Relaxed Alert

Person has a relaxed level of awareness

Starts to observe existing conditions and changing environment

Knows when something doesn’t “look or feel right”

A potential threat makes the person focus on observing details

Person is capable of broad risk evaluation, based on observations

Capable of preparing to make decisions to act

Identify the adversary (hazard)

Heart Beat: 80-100 BPM

Example: Becomes aware of location of all exits, entrances and evaluates them from primary, secondary, tertiary values

ORANGE: Imminent Alert

Person obtains a heightened awareness of a specific threat in time and place

Aware that something doesn’t “look or feel right”

Notices what is changing in immediate area (time and place)

Detects when someone/something is not acting right for the situation

Compiles objective evidence to identify the adversary/hazard but not sufficient to trigger action

Fine tunes options for imminent action

Heart Rate: 100-115 BPM

Example: Adversary wearing a long wool coat in July

RED: Action Alert

Person has made a decision to trigger precise actions

Reduced concern for success/failure outcome

Extreme focus on target/hazard will limit awareness of broader environment

No hesitation at trigger point regardless of effect — no turning back, just forward

Hope for the best, prepare for the worst

Adrenaline heightens eye-hand coordination, slows temporal vision

Heart Rate: 115-140 BPM

Example: Run, hide or fight

The fact remains that we are all flawed humans and Murphy’s Law has yet to be repealed. The author Robert Ludlum would undoubtedly propose in a “Jason Borne Threat Management System” a fifth (and ultimately final) stage of S/A:

BLACK: Panic Level

Despite careful preparation, all tactics fail to terminate the threat/hazard

Person becomes “frozen” in systemic shock

Experiences a breakdown of mental capacity and physical performance

System overload cancels out “fight or flight” response

Victim rapidly succumbs to the threat agent or hazard source

Heart Rate: 145-175-plus BPM

Example: Coma, collapse or death

I call the reader’s attention to these levels of alert because S/A is neither simple nor easy to achieve without knowing and practicing them regularly. There are several other “feedback” models of S/A utilizing more systemic analysis, evaluation and verification in use on macro levels, but Cooper’s model is what military and first responders find works best for those with boots on the ground.

It’s important to remind yourself is that no one becomes an expert in S/A. At best, we become dedicated practitioners over time. Everyone who practices S/A consistently realizes that it seldom has the same shape or outcome every time. But in the moments before either an attack or an accident, awareness is always better than ignorance.

Loss or Decay of Situational Awareness

Mr. Cooper’s training tries to clarify the human nature of the hunter-and-prey relationship. In doing so, it eliminates the unexpected and provides alternative outcomes based on the individual’s decision to act on observations. It also prepares the person for the diabolical “reversal of fortune” event, inevitably caused by either the decay or total loss of S/A by the practitioner. The following non-inclusive items may contribute to a person’s slow or rapid loss of situational awareness:

Ignoring your intuition (“gut feeling”). The head has a tendency to lie at high volume, while the gut is incapable.

Allowing in distractions (loss of focus). Abort the mission between the second and third distraction.

Fatigue. Peak physical and mental capabilities required for successful S/A. Steering wheel naps are recommended.

Feeling inadequate (negativity). Visualize success and it will materialize. Blind hope is self-defeating.

Breakdown of self-communication. Keep an open line with yourself through S/A.

Rushing through the alert levels. Shed self-imposed deadlines like you would wet clothes. Remember; “Slow is smooth and smooth is fast.”

Task saturation. Keep-it-simple-stupid!

Attempting new tasks under unreasonable time pressure

Failing to follow the plan

Violating the three Personal Prime Directives:

Failure is not an option.

Never give up.

Everyone dies, just not now.

Regaining Lost S/A

Mr. Cooper was a realist if nothing else. He had clear expectations for us humans. In preparation for S/A, one shall always include viable solutions for potential loss of S/A. How can we regain individual S/A once it has begun to decay or evaporated entirely? The following suggestions will certainly aid in S/A recovery:

Delay the mission. Unless a life is clearly in the balance, nothing is all that critical

Reduce the workload to regain your span of control

Reduce the threat level. Step out of the batter’s box

Improve self-communication skills

Improve concentration skills

Stick to the plan

Meditate any time. Learn the importance of centering your breathing

Don’t pray for rescue. Give thanks for success so far

>> SIDEBAR

“Whether you are a laborer, mechanic, middle management or project supervisor, the benefits of a “relaxed focus” on today’s acts and conditions has positive effects on everyone’s personal safety and health, the quality of your work product, as well as overall productivity.”

Applicability

So, what exactly does Cooper’s four Levels of Alert have to do with construction work? How and where does S/A fit in your toolbelt every shift? As a safety inspector auditing safety and health on both large and small jobsites, I count on my version of S/A to keep me focused on the details and comfortable with the responsibility to act on other’s behalf. In particular, the practice of self-communication that occurs while conducting my version of S/A helps to:

Keep me honest (avoid assumptions)

Avoid tunnel vision (a well-camouflaged distraction)

Anchor me in the present (here-and-now) experience

Keep me relaxed in any environment

Clarify details I might have otherwise missed

Give me confidence in my skills to observe, act and verify

Make me more effective in my own actions

Whether you are a laborer, mechanic, middle management or project supervisor, the benefits of a “relaxed focus” on today’s acts and conditions has positive effects on everyone’s personal safety and health, the quality of your work product, as well as overall productivity. You should carry S/A in your holster, not leave it in the gang-box.

It’s reasonable to expect more than a few obstacles along the winding path to S/A. Rewards still require sacrifices. Remember “no pain, no gain”? Your old high school wrestling coach was actually handing you the key, when you thought he was making you miss the last bus.

Chip Macdonald of Best Safety LLC in Cambridge, N.Y., offers safety training, program implementation and management tailored to companies of all sizes. He can be reached at 518-461-3358 or bestsafe@capital.net.